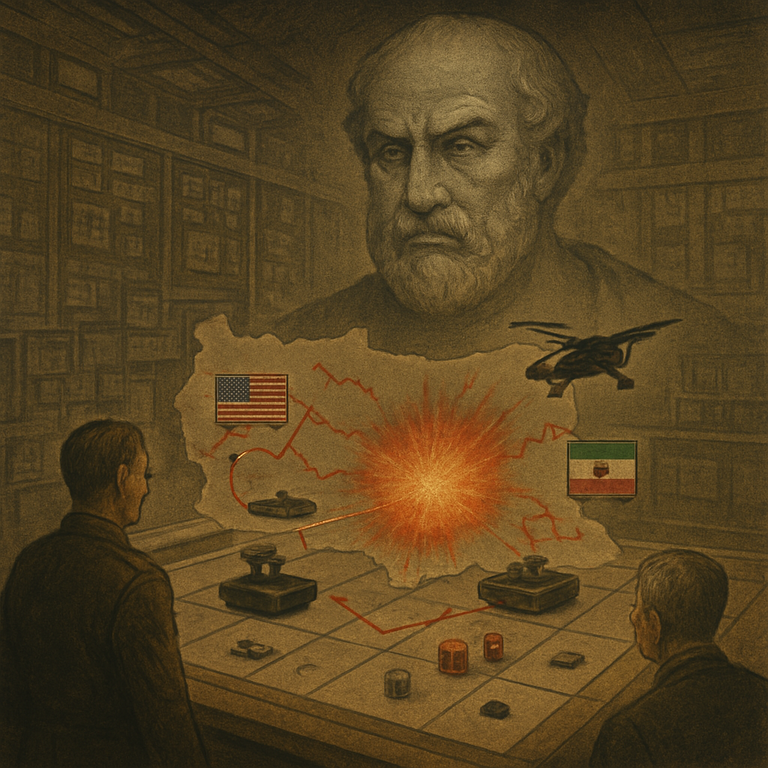

Iran: The Empire's Final Trap

This article argues that while China is the primary challenger to U.S. hegemony, a conflict with Iran—sparked by Israeli escalation or miscalculation—could fatally weaken the American-led world order. Drawing on the Thucydides Trap and Mearsheimer’s theory of power, it demonstrates how U.S. demographic decline, deindustrialization, and overextension make victory in a prolonged Middle Eastern war unlikely. An AI-assisted conflict simulation reveals that such a war would likely unfold in two phases: a failed U.S./Israeli strike on Iran, followed by a devastating hybrid conflict. The resulting erosion of American credibility would accelerate the defection of Asian allies to China, hastening the Western Empire’s collapse. Ultimately, the article warns that Iran, not China, may prove to be the trap that brings down Pax Americana.

Introduction

The Thucydides Trap—the perilous dynamic when a rising power threatens to displace a ruling one—has long framed U.S.-China rivalry as the defining contest of the 21st century. Yet history teaches that empires rarely collapse in head-on clashes with their peers. Instead, they unravel through overreach in secondary conflicts, where weaknesses are exposed and credibility shattered. Today, Iran—not China—poses the gravest risk to the American-led order. A U.S. war with Iran, whether sparked by Israeli provocation or miscalculation, would reveal the hollowness of Washington’s power: depleted arsenals, feeble industrial capacity, and allies questioning its resolve. As Asian partners witness America struggling against a middleweight adversary, their pivot to China would accelerate, turning Tehran’s defiance into the trap that snaps shut on Pax Americana.

This article applies Thucydidean logic to argue that Iran, not China, could catalyze the Western Empire’s demise. Drawing on conflict simulations, John Mearsheimer’s theories of power, and the lessons of history, it warns that a war Washington cannot “win” would doom its position in Asia—and with it, the postwar order.

The Thucydides Trap: A Primer

The Peloponnesian War’s central lesson—recorded by Thucydides in 431 BCE—was that Sparta’s fear of Athens’ rise made war inevitable, regardless of either side’s intentions. This dynamic, later termed the Thucydides Trap by Graham Allison, reveals a recurring pattern in history: when a rising power threatens to displace an established one, the structural tension frequently leads to conflict, even when both seek to avoid it. Of the 16 historical cases where such a power transition occurred, war followed in 12—not always through direct confrontation, but often through cascading crises that exposed the ruling power’s overextension.

The most consequential example is not a modern proxy war, but Rome’s disastrous invasion of Parthia (53 BCE). Rome, then the unrivaled superpower of the Mediterranean, sought to crush the rising Parthian Empire in a swift campaign. Instead, the Battle of Carrhae became one of history’s most devastating defeats—not just militarily, but politically. The loss of legions and prestige emboldened Rome’s rivals, drained its treasury, and accelerated internal decay. Though Rome survived for centuries, Carrhae marked the beginning of its imperial overreach, proving that even a hegemon’s secondary conflicts can trigger irreversible decline.

Similarly, Napoleon’s invasion of Spain (1808)—a war meant to consolidate French dominance—became the "ulcer" that drained his empire. The Spanish insurgency tied down French troops, emboldened Britain, and exposed Napoleon’s strategic fragility. Neither Parthia nor Spain were peer competitors to Rome or France, yet their resistance proved catastrophic.

The Thucydides Trap, then, is not merely about great-power wars. It is about the illusion of strength—when a hegemon’s overcommitment to peripheral conflicts reveals its core weaknesses. Today, as China rises, the U.S. faces not just a direct challenger, but the risk of being lured into a draining conflict with Iran, one that could, like Carrhae or Spain, hasten the unravelling of an empire.

Decline of the Western Empire: A Mearsheimian diagnosis

John Mearsheimer, the preeminent theorist of structural realism, argues that sustainable power rests on two irreducible pillars: population and wealth. The former demands not just numbers, but cohesion; the latter is not measured in paper currency or stock indices, but in a state’s capacity to produce—to mobilize resources, forge weapons, and sustain its people through crisis. By this metric, the U.S.-led Western order is faltering, its weaknesses magnified by the very forces that once made it dominant.

Demographic Decay

America and its core allies face a dual crisis: aging populations and shrinking labor forces. By 2050, nearly 25% of Americans will be over 65, mirroring trends in Europe and Japan. Unlike China—which retains a disciplined, productive workforce despite its own demographic cliff—or Iran, where 60% of the population is under 30, the West relies on immigration to fill gaps. Yet this fix is politically fraught, straining social cohesion and diverting resources from long-term planning. A state that cannot regenerate its people, cannot regenerate its power.

The Mirage of Wealth

The U.S. economy, once the arsenal of democracy, has been hollowed out by financialization. Wealth today resides not in factories or shipyards, but in speculative markets and debt-fueled consumption. Consider the munitions crisis exposed by the Ukraine war: The U.S. produces just 30,000 artillery shells monthly—a fraction of Russia’s output and far below the 80,000 Ukraine expends in a single month. To arm Taiwan in a conflict with China, the Pentagon estimates it would need 5-10 years to rebuild stockpiles. Against Iran, a regime that has stockpiled missiles and drones while mastering asymmetric warfare, America’s depleted arsenals and atrophied defense-industrial base would face immediate strain.

Geostrategic Overreach

The U.S. today resembles Rome on the eve of Carrhae: stretched thin by simultaneous commitments to Europe (against Russia), Asia (against China), and the Middle East. Russia’s resilience in Ukraine has already fractured NATO unity, with European allies questioning Washington’s ability to defend them. A war with Iran—a protracted conflict involving missile barrages, naval blockades, and cyberattacks—would force the Pentagon to triage resources. Asian allies, watching America struggle against a regional power, would confront a grim calculus: If the U.S. cannot deter Tehran, how could it deter Beijing?

Mearsheimer’s framework leaves little room for sentiment: Power is structural, and decline is often masked until crisis strikes. The U.S. still boasts the world’s largest economy and military, but its inability to produce—whether soldiers, missiles, munitions, or consensus—has turned its strengths into liabilities. Iran, by contrast, has spent decades preparing for a war of attrition, one where patience, proxies, and production matter more than carrier groups. In such a contest, the Thucydides Trap springs not from China’s rise, but from the West’s inability to reconcile its ambitions with its decay.

US-Iranian Conflict: An AI-Powered Wargaming Exercise

The Thucydides Trap traditionally frames great power competition as the primary threat to international order. However, history demonstrates that secondary conflicts often prove more dangerous to hegemonic powers than peer competitors. The Roman Empire suffered its most consequential defeat not against Parthia, but at Carrhae. Napoleon's downfall began not with Russia, but in Spain. To examine whether contemporary America faces a similar dynamic, the NWISS conducted an AI-powered wargame of a US-Israeli conflict with Iran. The results reveal how a regional confrontation could precipitate global systemic collapse through mechanisms far more complex than traditional military analysis predicts.

Methodological Framework

The simulation employed NWISS's five-phase analytical process, combining artificial intelligence with expert human oversight. Generative AI first constructed baseline scenarios using historical conflict data, including the 2002 Millennium Challenge's asymmetric warfare lessons and the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh drone warfare precedents. Human analysts then refined these models, incorporating real-world constraints such as MIT Professor Theodore Postol's findings on missile defense inefficacy and post-2024 Hezbollah organizational dynamics following Hassan Nasrallah's assassination. This hybrid approach proved particularly valuable in capturing the nonlinear escalation pathways characteristic of modern hybrid warfare, where cyber operations, economic disruption, and proxy forces interact in unpredictable ways.

Scenario Architecture

The simulation's trigger event centered on a US-Israeli preemptive strike against Iranian nuclear facilities, justified through a fabricated connection between Houthi militants and Tehran's nuclear program. Phase One unfolded across a compressed 72-hour timeline, with stealth aircraft targeting Fordow's underground enrichment halls and Natanz's centrifuge arrays. Iranian retaliation manifested immediately through ballistic missile salvos against regional US bases and Israeli population centers, achieving significantly higher penetration rates than conventional military assessments predicted due to the limitations of Iron Dome and Patriot systems.

Phase Two transitioned to sustained hybrid conflict, where traditional military engagements became secondary to economic and informational warfare. Iran's strategic mining of the Strait of Hormuz created immediate global energy shocks, while carefully calibrated cyberattacks disrupted Saudi oil infrastructure and American electrical grids. Proxy networks demonstrated remarkable coordination, with Hezbollah rocket barrages overwhelming Israeli civil defenses as Iraqi militia drones harassed US forces. The simulation particularly highlighted how these asymmetric tactics created compounding effects - each successful attack eroded coalition political will while strengthening Iran's deterrence credibility.

Force Structures and Their Limitations

The order of battle analysis revealed critical asymmetries between conventional military power and actual strategic effectiveness. While the US-Israeli coalition maintained overwhelming advantages in stealth aircraft, precision munitions, and naval assets, these capabilities proved poorly suited to the conflict's evolving character. Carrier strike groups, for instance, became vulnerable to swarming drone attacks, while advanced fighter aircraft lacked targets against Iran's dispersed proxy networks.

Conversely, Iran's forces demonstrated how limited but well-applied capabilities could achieve disproportionate effects. Russian-supplied S-400 systems complicated initial strike operations, while relatively unsophisticated naval mines and anti-ship missiles effectively closed the Persian Gulf to commercial traffic. Most significantly, the simulation confirmed that Iran's proxy network architecture - often dismissed as a terrorist nuisance in conventional analysis - functioned as a genuine force multiplier, allowing Tehran to project power while maintaining plausible deniability.

Strategic Outcomes Assessment

The battle damage assessment quantified consequences that extended far beyond traditional military metrics:

| Category | US/Israel | Iran |

|---|---|---|

| Military | 450 casualties, 12 F-35Is lost | 40% strategic missile inventory expended |

| Economic | $2.8 trillion global recession impact | $12 billion infrastructure damage |

| Political | Alliance cohesion fractured | BRICS expansion with Saudi accession |

These numbers only partially capture the strategic reality. The economic warfare dimension proved particularly devastating, as oil price shocks triggered secondary effects across global markets. Perhaps more consequentially, the political fallout demonstrated how regional conflicts can unravel decades of alliance architecture, with European partners distancing themselves from American unilateralism while Asian allies quietly realigned toward China.

Strategic Implications

Four fundamental insights emerge from the simulation that challenge conventional strategic thinking. First, the proxy warfare advantage has fundamentally altered the calculus of regional conflicts. Iran demonstrated that non-state actors, when properly integrated into a national security strategy, can effectively counterbalance conventional military superiority through sustained attrition and psychological impact.

Second, economic interconnectedness has created a domino effect in modern conflict, where targeted disruptions trigger unpredictable systemic consequences. Just as a single falling domino can topple an entire chain, the simulation demonstrated how actions against critical chokepoints like Hormuz initiate cascading failures across financial markets, supply chains, and political alliances. These ripple effects rapidly exceed their original tactical purpose, transforming limited military engagements into global crises.

Third, the Thucydides Trap manifests most dangerously not through direct great power confrontation, but through secondary conflicts that reveal systemic vulnerabilities. While China remains America's primary strategic competitor, the simulation demonstrated how a conflict with Iran could accelerate American decline more effectively than any Chinese action by exposing military overstretch, economic fragility, and diplomatic isolation simultaneously.

Finally, the diplomatic consequences of kinetic action have become strategically decisive. Even successful military operations generated such severe political blowback that they undermined America's global position. This suggests that in an era of multipolarity and economic interdependence, traditional measures of battlefield success have become dangerously disconnected from long-term strategic outcomes.

Conclusion

The wargame's most sobering revelation was not military but systemic: the United States remains trapped in a strategic paradigm that prioritizes conventional dominance while adversaries have moved beyond it. Iran's ability to transform a regional conflict into a global crisis through hybrid warfare demonstrates how secondary powers can exploit the very interconnectedness that underpins American hegemony. For policymakers, this demands a fundamental reevaluation of strategic priorities - not because Iran represents an existential threat, but because the mechanisms of modern conflict make peripheral engagements potentially as destabilizing than central ones. In an age where economic warfare proves more decisive than air superiority, and proxy networks just as resilient as armored divisions, the real Thucydides Trap may be failing to recognize how profoundly the rules of great power competition have changed.

Comments ()